In the 2004 comedy Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story, we knew who to root for. It wasn’t the shiny, sculpted Globo Gym. It was Average Joe’s. A ragtag group of misfits who scraped their way to glory not because they were better, but because they had heart. They had grit. They had nothing to lose and everything to prove.

Two decades later, the spirit of Average Joe’s is gone. In dodgeball, in baseball, and in America.

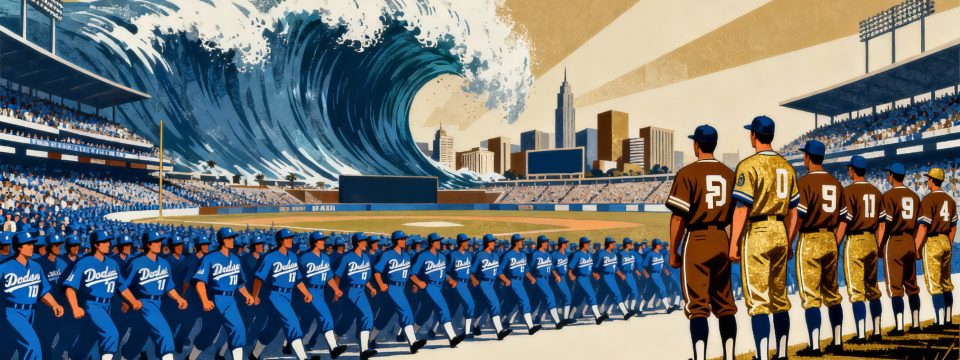

The Dodgers Are Globo Gym Now

I’m a native San Diegan. I was born here. I grew up watching the Padres, believing in the magic of possibility. That was the entire pitch: keep the faith. Maybe this little team could one day shock the world. Our hope was always outsized, but it was real. And the community built around that hope was real too. We weren’t promised trophies. We were promised a shot.

That promise feels meaningless now.

The Dodgers are what Globo Gym warned us about: a $700 million man in Shohei Ohtani. They deferred most of his money, exploited the luxury tax, and somehow made it look clean. And guess what? It already paid off. One year in, and it’s a bargain.

It’s good business to be the Dodgers. Be perfect. Be ruthless. Recruit the best, spend the most, defer the most, and win. Not just now, but forever. Because here’s the scary part: this works. Ohtani is the blueprint. Every elite free agent is watching. Want to win? Go to the Dodgers. Want to get paid and compete? They’ll find a way. And they’ll only get more powerful from here.

We Can’t Even Keep Our Own

I have family that are Dodgers fans. Friends too. That’s expected in any rivalry, but what’s different in San Diego is how often we lose our own.

People born here. People raised on Tony Gwynn and Trevor Time. People who should know better.

Even some of our own heroes leave and don’t come back. Adrian Gonzalez was born in San Diego. He became a Padre. Then became a Dodger. Now he’s a Dodger fan. That’s not a knock on him. That’s the gravity of L.A.’s machine. You don’t see it go the other way. No one starts as a Dodger and ends up a Padre fan, except my wife.

Even Mario Lopez—Slater, for crying out loud—was born here. But what hat is he wearing every October?

San Diego doesn’t just battle payrolls. We battle memory loss.

The Southern Dodgers

Some Dodger fans call the Padres the Southern Dodgers — like it’s a joke, a backhanded compliment, or proof of conquest. My father-in-law, who grew up in Los Angeles and still lives there, says it with a smirk when he’s in town. To him, it’s just part of the rivalry. To us, it’s a reminder that our own team gets treated like their satellite franchise.

When the Dodgers come to Petco Park, it stops feeling like a rivalry and starts feeling like an invasion. The stadium turns blue. The chants get louder. The fights in the stands become more frequent. It doesn’t feel like home-field advantage. It doesn’t even feel neutral. It feels like we’re guests in our own ballpark.

People from Los Angeles often don’t understand why this rivalry runs so deep for San Diegans. To them, we’re just another team in the division. To us, they’re bullies. Big-market. Big-brother. Always on TV. They win the headlines, they buy the stars, and they walk into our city like they own it. And sometimes, they do.

Because for us, it’s not just about baseball. It’s about identity. We only have the Padres. That’s it. Los Angeles already took our only NFL team. The Chargers were ours, and now they play in a stadium paid for by L.A. fans. So when the Dodgers come to town and flood our stadium in blue, it’s not just a game — it’s a reminder of everything we’ve had taken from us.

What makes it worse is that many Padres season-ticket holders end up selling their seats for those games — not because they want to sell to Dodger fans, but because Dodger fans are the ones who buy. That’s the market. And so Petco becomes Chavez Ravine South, not by design, but by demand.

You go to a Padres–Dodgers game in San Diego and look around. It’s not 50/50. It’s more like 70 percent Dodger fans. It’s a home game for them. In our house.

And it’s not just inside the stadium. There have been nights when the streets of downtown San Diego look like a Dodger parade — thousands of fans in blue marching through the Gaslamp Quarter, waving flags, chanting, and treating it like they’ve just won the World Series. It’s loud. It’s rowdy. It’s exhausting. And it’s right in the heart of our city.

And yeah, we’re still supposed to keep the faith.

When Winning Became a Science Experiment

What’s lost in all this isn’t just the underdog. It’s the soul of the sport. Baseball used to be messy. It was drama and dirt and bad hops and unscripted heroics. Now it’s algorithmic matchups and biomechanical swings. It’s not a game. It’s a formula.

And when the richest team perfects the formula, what are we left with? A league where most teams are just narrative filler for the one team built to win every October.

We turned the pastime into a spreadsheet. We turned the joy into a yield curve. And the Dodgers? They’re just the final form of a sport that sold its soul to the model.

There’s a popular take going around right now that the Dodgers aren’t the problem. That they’re just the team that reinvests their revenue properly. That if other teams spent like they did, everything would be fine.

That’s a fantasy.

The Dodgers aren’t just reinvesting more. They’re operating with a fundamentally different economic engine. Their long-term TV deal, reportedly putting $330 million a year into their coffers, gives them a scale of revenue most teams can’t even dream of. It doesn’t literally erase their payroll, but it tilts the field so sharply in their favor that “covering payroll” becomes a realistic outcome for them, even though it’s fantasy for most franchises. That’s a revenue stream most teams, including the Padres, do not have at all. San Diego currently has zero dollars coming in from a TV deal. We’re not talking about strategy. We’re talking about scale.

This isn’t about owners being cheap. It’s about a system so imbalanced that one team has near-unlimited money. And the league does absolutely nothing to level the playing field. There’s no salary cap. No meaningful revenue sharing. No attempt at competitive balance. Just a shrug and a suggestion to “try harder.”

Sure, baseball technically has a luxury tax. But for the Dodgers, it isn’t even a speed bump. It’s just the cost of doing business. And business is booming.

And they know it, too. After the Dodgers clinched the National League pennant in 2025, manager Dave Roberts looked right into the camera and said:

“Before the season started, they said the Dodgers are ruining baseball. Let’s get four more wins and really ruin baseball.”

He meant it as a joke. A cheeky little dig at the critics. But here’s the thing: he’s right. They are ruining baseball. Not because they’re cheating or breaking rules, but because the system rewards exactly what they’ve mastered. They are the final form of a sport that favors media markets, luxury tax loopholes, and algorithmic perfection over competition.

Need proof? The team they beat in that series, the Milwaukee Brewers, represents a city of about 575,000 people. The Dodgers draw from a regional population of over 20 million. One is a community. The other is a worldwide media empire. And MLB acts like it’s a fair fight.

The Dodgers didn’t break the game. Baseball handed them the blueprint. And now they’ve become Globo Gym. They know it. And they’re proud of it

But trying harder won’t make San Diego a media market the size of L.A. Trying harder won’t summon a billion-dollar brand overnight. And trying harder definitely won’t sign Shohei Ohtani to a deferred super-contract where the luxury tax barely notices.

This isn’t about effort. It’s about gravity. And right now, baseball is built to bend toward L.A.

A Mirror to the Culture

This isn’t just a Dodgers problem. It’s a cultural one.

Somewhere along the way, we stopped cheering for the team that tried hardest and started worshiping the team that bought the best. We replaced “do more with less” with “why try if you don’t have it all?”

It’s not just baseball. It’s startups. It’s college. It’s politics. It’s the kid with a dream versus the kid with legacy admission and a trust fund. It’s not about grit anymore. It’s about glow.

And the Dodgers are the glow. All of it.

The glow is that high-gloss illusion of success — the curated, data-driven, brand-safe version of greatness. It’s not about heart. It’s about polish. It’s about looking unbeatable before the game even starts. It feels inevitable. Predictable. And maybe worst of all, boring.

Fifty Years of Faith

My family has had Padres season tickets for fifty years.

Half a century of summers at the ballpark. Hope, heartbreak, and holding on to something that felt bigger than wins and losses. I’ve never once questioned keeping those tickets. Never even thought about it. Until now.

In the past four seasons alone, Padres season-ticket prices have jumped again and again: about 20% in 2022, 18% in 2023, 9% in 2024, and now another 3% in 2025. That’s more than 50% higher than just a few years ago. And what do we get for it? No backpacks in the ballpark. No outside food. More rules. More security. A parking space for the cost of a mortgage payment. Longer lines. No championships. And a sport that feels like it doesn’t even like its own fans anymore.

And it’s not because of what the Padres are doing. It’s what Major League Baseball is becoming.

The sport I grew up loving feels like it’s stopped being about the game and started being about the transaction. About absorbing as much money as possible, not building a community around a shared love of the game.

I definitely can’t afford $18 beers. And it feels like I’m not really welcome unless I can.

Fifty years of tickets should feel like an investment in tradition. Lately, it feels more like a subscription to a machine that no longer remembers why it was built.

Fast indexing of website pages and backlinks on Google https://is.gd/r7kPlC

Fast indexing of website pages and backlinks on Google https://is.gd/r7kPlC

Turn your traffic into cash—join our affiliate program!